Bret Anthony Johnston’s outward appearance oozes fiction writer. You see his thick-rimmed glasses and often solemn photos and you think, Yup, this is what they’re all like. But Johnston (whose name sounds a little like a boy band member, doesn’t it?) is so much more than the scarf-wearing stereotype you might associate with the typical writer. His background – before the famed Iowa Writers’ Workshop and his post as Director of Creative Writing at Harvard – is in professional skateboarding, the regular-Joe aspect making him as genuine and sincere to any wannabe writer who comes in his path, with zero trace of arrogance to be found.

I know him from the Iowa Summer Writing Festival, where I enjoyed hearing him speak to a roomful of wannabe writers (myself included). When I met him afterward, curious about pursuing an MFA at a younger age than what I had been told was appropriate, he was all support and kind. Through a series of emails in the following years, he was the cheerleader I needed to get past my doubts about MFAs ,and my most importantly, he instilled the importance of “ass-in-chair time” – actually sitting down and Something I still think about today.

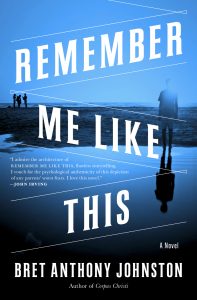

Bret Anthony Johnston’s new book, Remember Me Like This, has the page-flipping excitement of Gillian Flynn’s Gone Girl in addition to the ruthless attention to detail and heart-touching soul that permeates his short stories.

Q: As the head of the Creative Writing Department at Harvard, I imagine your daily life is quite busy. What’s your writing routine like?

A: I tend to write in the morning, then revise in the afternoon. I rarely reread anything I’ve written until I’ve finished the draft for fear of getting bogged down in a sentence or scene that will very likely get cut. The end of the story or novel is always a surprise to me; in the few case when a narrative has ended in the way that I expected or planned, I’ve been gravely disappointed. Once I have a draft with a workable beginning, middle, and end, I spend countless hours on the structure and language, all while delving deeper into the characters. My routine is inefficient and messy, but I’m equally patient and stubborn. I work rigorously and consistently, which allows my imagination to work irresponsibly. I think that’s what you want as a writer—to allow your imagination the freedom to make unexpected connections and lead you down new and rewarding channels.

Q: Animals (dolphins, dogs, snakes) play a major role in your new novel. Are you a huge animal lover?

A: You have no idea! For every animal in my fiction, I’ve cut five out. Most nights before bed, I read about different animals—everything from birds to chupacabras—and I have to actively discourage myself from folding every fascinating thing I’ve learned into my fiction. I don’t always succeed. When there’s not an animal in a story—mine or another writer’s—I feel a particular kind of loneliness. It’s like walking into a house that lacks a dog or cat or parrot or python.

Q: There is also a quite a bit of detail around food. Is this a big part of Southern culture? Or are you just really into food?

A: Food is certainly a part of Southern Culture, and the food in South Texas is like nothing you can find elsewhere, so I’m certainly trying to evoke the place and people in that way, but there’s also a far more mundane and practical strategy here. Writers reach the readers through their senses, and food is a reliable way to draw the reader closer. If you show a character scrambling eggs in a cast-iron skillet, if you can evoke the snap and sizzle of the grease, then you can likely tap into a reader’s memory. They lean closer, trying to smell the smoke. There’s something Pavlovian about it, I think. Either that, or I’m always hungry when I write.

Q: How did you know that your idea for Remember Me Like This was a big enough plot for a novel? Was it a short story first?

Q: How did you know that your idea for Remember Me Like This was a big enough plot for a novel? Was it a short story first?

A: I tend to look at this subject through the lens of curiosity. When I get an idea, I try to gauge how long it will take to satisfy my—and, I hope, the reader’s—curiosity about the characters and their conflicts. With Remember Me Like This, I immediately recognized the gravity of the situation, the breadth and complexity, as material that would require a novel. I didn’t think I could give the readers everything they’d need in a short story. Like many writers, I’ve written stories that cover more time than this novel does, but I knew that various scenes would take hundreds of pages to ensure that the reader was prepared to absorb the impact. I was curious enough about the characters to spend that time with them, and daily I coaxed myself into believing the readers would share that curiosity.

Q: Your book, Naming The World, encourages fiction writers to do extensive research on their subject to craft the most realistic world possible. What kind of research did you do for Remember Me Like This? Several of the scenes with Alice and the Marine Lab were extremely detailed.

A: In my workshops at Harvard, I require my students to include research in their stories—if they don’t, they risk failing—and I’ve never seen it do anything except elevate the fiction. I’d like to believe it serves my work in the same way. I did a lot of research for the novel, not least with the dolphin sections. I’ve read countless books on dolphins, and I’ve volunteered in the same way that Laura does in the novel—my version of method acting. I also researched teaching Texas history classes, working in pawnshops, kidnapping, the subjects of law and child psychology, and dry-cleaning. I read a whole book on dry-cleaning, and I’d say about one sentence of what I learned remains in the novel. Still, it felt important to do it. I had to learn everything I could to get that one sentence in there.

Q: Your work is often centered around where you grew up, in and around Corpus Christi, Texas. Do you ever get the urge to write about other places you’ve lived?

A: The longer I’m away from south Texas, the more interested I become. When I lived there, I took the landscape and the stories the landscape offers for granted. I was blind to it, perhaps willfully so. Having been away for so long now, I’m more fascinated by the area than ever. I feel as though I see it clearly and that clarity sparks my imagination. Maybe the other places will start to ignite my curiosity, but it hasn’t happened yet.

Q: What’s the most important advice you can give to a writer?

A: Log the hours. Don’t romanticize the vocation. Understand that the labor should be viewed in the same way that a job hanging drywall is. You show up for work, work as hard and thoroughly as you can, and you don’t rush the process. Little by little, the job gets done. Be patient. Be rigorous. Write the book you want to read that isn’t on the shelf yet.

~Kat Vetrano

*Photo credit: Bret Anthony Johnston